Just outside York’s city walls is England’s oldest continuing convent. Its roots lie in the missionary vision of Mary Ward, a child in the city when Margaret Clitherow was executed – crushed to death – for having hidden Roman Catholic priests and allowed the celebration of Mass in her house. It was a powerful early experience for a life which saw Ward, in 1609, found the Congregation of Jesus, an order modelled on the Jesuits, and underpinned with a belief that women could play a full and active role in mission and education work. It met with opposition within the Roman Catholic church and found itself suppressed by Pope Urban VIII (Ward herself was imprisoned at one point by the Inquisition, and the order didn’t in fact receive the definitive approval of the Church until 1877).

All of which makes the existence, let alone continuance, of the congregation’s York home all the more remarkable. It was founded by one of her followers, Frances Bedingfield, in 1686 as a school for Catholic girls. The establishment of a Catholic convent was at this time illegal – the nuns concealed their identity, but even so faced persecution and imprisonment. Yet the convent persevered, the 18th century seeing the original house replaced by today’s Georgian building and, in 1769, the construction of the elegant neo-classical chapel. This was still 22 years before the Roman Catholic Relief Act of 1791, which finally allowed worship to officially take place in the convent. Consequently the chapel is entirely hidden from the outside, its domed roof disguised by a pitched slate one above it. As a further precaution, eight exits were built to offer priests an escape route in the case of a raid, and even a (recently-rediscovered) priest hole for them to hide in.

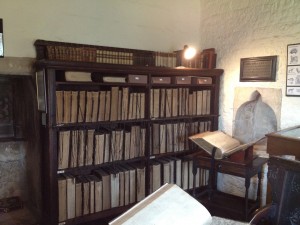

The 20th century saw the school become first a grammar, then a comprehensive, and it is no longer run by the convent. But what remains is a home for members of the Society of the Congregation of Jesus. The convent’s history is told in a museum, while the convent also serves as a small guesthouse and cafe (the well-maintained gardens are a tranquil escape from the city outside). It’s a calming place for prayer or just peace imbued with a spirit of hospitality, and a living testimony to the courage of so many in witnessing to their faith against the odds.