Built in 1840 by George Watson Buck, Stockport viaduct’s 27 arches span a third of a mile, reach to a height of 111 feet and use 11 million bricks. At the time of construction it was claimed to be the largest viaduct in the world.

Graceful in its solidity and might, elegant in its uniformity of form and colour, if it spanned a rural valley it would set off a scene of picturesque beauty. As it is, positioned high above an industrial town, it has instead earned a place in paintings by the urban chroniclers LS Lowry and Alan Lowndes.

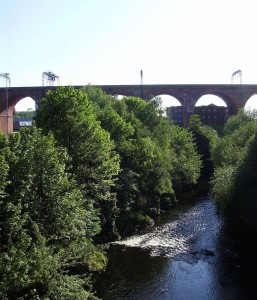

To one side, far below, lies the town’s bus station, the double-deckers dwarfed by the colossal arches. A little way to the other side, the distinctive glass pyramid of the Co-operative bank emits its sci-fi glow. Beneath runs the M60 and flows the River Mersey, a mere hint of the vast estuary it will become by the time it reaches Liverpool. Close by, sharing the same rust-red hue, is the chimney of Hat Works, a Victorian Mill-turned museum and another fine remembrance of Stockport’s industrial heritage.

But paradoxically, perhaps its remarkable stature is best appreciated when you can’t see it – by hopping on a train at Stockport station, just on the southern side, and travelling atop the viaduct towards Manchester. Which is something you will always be able to do: a local story goes that when plans were announced a few years ago to cut the number of trains stopping here, a local councillor cited an Act of Parliament from the time of the viaduct’s construction stating that any service wanting to use it had to stop at Stockport. An extra reason for the town to be proud of its iconic landmark.